Pavel Sviardlou: Nowadays, Everyone is a Journalist in Belarus

Pavel Sviardlou, Euroradio’s Editor-in-Chief

A clean-up, a carpet bombing, a pogrom. These are the words Belarusian journalists use these days to describe the increasing government attacks on journalism. Being a reporter has never been easy in the country, but the pressure escalated last year. On August 9, 2020, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who had irremovably ruled Belarus for 26 years, was declared the presidential election winner with over 80% votes. But neither Belarusians nor the international community believed the official numbers. During the electoral campaign, all potential contenders were either arrested or forced into exile, like dozens of activists, journalists, and bloggers.

Outraged by massive election rigging, hundreds of thousands in the 9-million nation took to the streets. Strikes began at key, mostly state-owned industrial enterprises. The government’s response to the peaceful protest was unprecedentedly violent, even by Belarusian standards. According to Amnesty International, over 30 000 people were detained, beaten, or tortured. Almost 600 people, including journalists, were recognized as political prisoners. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists, 33 media workers remain behind bars on charges ranging from economic crimes to state treason.

Over 25 years of Lukashenka’s authoritarian rule, Belarusian media operated in tough censorship and pressure conditions. Government attacks were common. For example, officials raided newsrooms during the crackdown after the 2010 presidential elections, with journalists and activists arrested en masse. But what is happening now, says Pavel Sviardlou, editor-in-chief of independent online broadcaster Euroradio, has crossed all the lines. “It’s a total mop-up [operation]. When we think we have finally hit rock-bottom, we fall further down, again.”

The Belarusian security forces carry out targeted operations against journalists. On May 23, 2021, Belarus authorities hijacked a Ryanair passenger plane flying over Belarus and detained Raman Pratasevich, former editor-in-chief of the country’s most popular Telegram channel. On May 18, police raided the offices of TUT.BY, the largest private and most popular online news outlet in the country. TUT.BY was not just a news portal; it was a ‘Belarusian Yahoo’ used by over 3 million people daily or more than 60% of internet users in Belarus. The website is blocked, with 12 employees remaining behind bars, including the editor-in-chief and chief accountant. In July, the remaining independent national and regional outlets faced massive searches and arrests. On July 8 alone, security officers raided 30 newsrooms and houses of journalists.

In this situation, says Sviardlou, independent media have only one strategy [which is] to survive. “To save yourself, keep as many of your people out of jails as possible, ensure their safety, relocate staff abroad. Still, one can’t count on anything these days. If security forces have not come for you today, they will come tomorrow. Hence, relocation. We also need to continue our work as much as possible.”

In the current crackdown, Euroradio may have faced the biggest challenge in its history. The radio station European Radio for Belarus (Euroradio) was founded in 2005 and began broadcasts in February 2006. Euroradio broadcasts in the Belarusian language across the whole country. Despite being established and run by Belarusian journalists, the radio station was forced to register as a Poland-based media outlet under increasing government pressure. In this bizarre situation, Belarusian journalists had to cover their own country as ‘foreign correspondents’ and seek annual accreditation by the government. In 2009, they managed to open a correspondent’s bureau in Minsk. In October 2020, the government revoked all accreditations for Euroradio journalists. On July 5, 2021, Belarusian authorities closed the bureau and, on August 9, blocked Euroradio’s website.

Many had doubts about this model during all 15 years of having two newsrooms – in Poland and Belarus, Sviardlou says. “People asked: why do you need an office in Warsaw? But now that “carpet bombing” or carpet detentions of fellow journalists are taking place in Belarus, we can use the Warsaw newsroom as a safe haven. That’s exactly why our news production and live interviews and chats with experts have continued uninterrupted.” Euroradio workers are relocating to Poland at the moment.

On the frontline

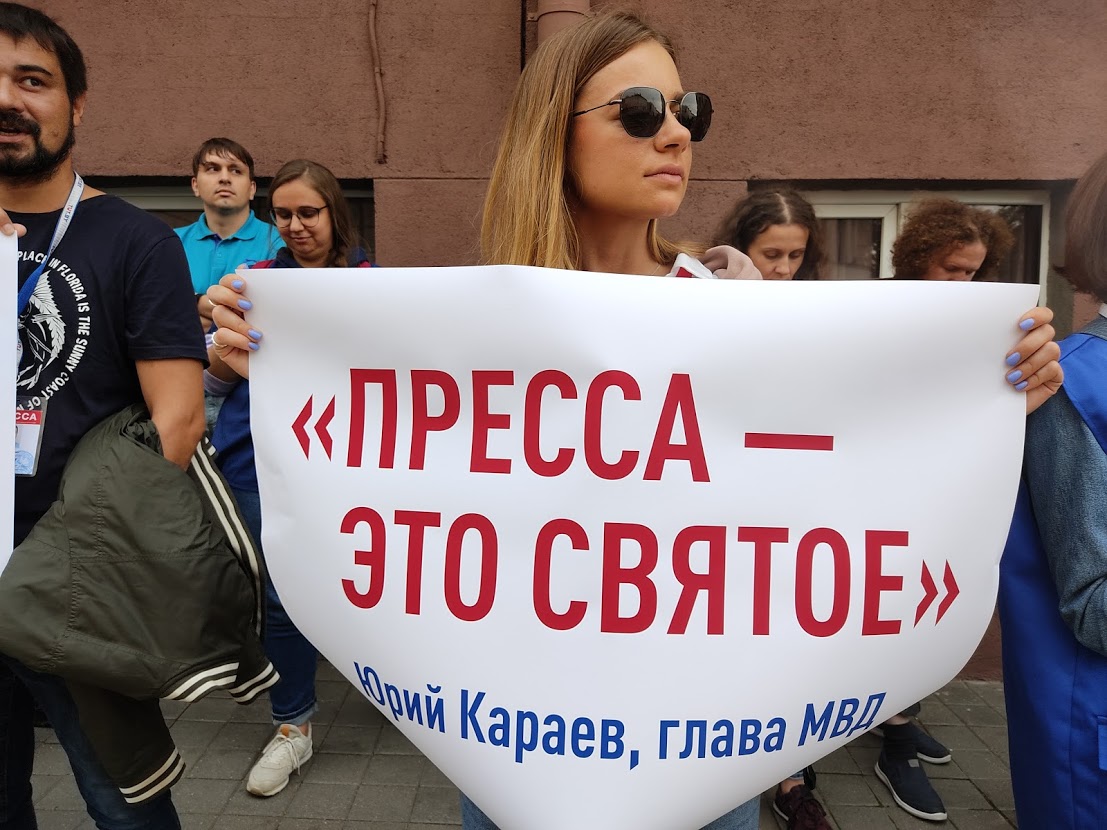

Can one talk about a viable news industry market where some journalists are behind bars, and some have fled Belarus? Many of them have simply lost their jobs because of repressions against independent media. The media environment, says Sviardlou, has somewhat broken into two unequal parts. A considerable segment of the so-called state-run journalism remains, with state journalists having unequal rights with independent media workers. The state media “obviously team up with security forces. They get video footage from police actions, including raids at independent newsrooms, interrogations of detainees,” Sviardlou points out. Doors are open for state media to attend political trials, while independent journalists have to wait outside. Besides, loyal journalists can attend mass protests, enjoying protection from the police. Independent journalists risk getting arrested for covering the same demonstrations. This applies not only to manifestations but to any happening in a public place. On May 18, 2021, when security agents were raiding TUT.BY’s office, Euroradio’s reporter Artem Mayourau was nearby. He saw that the operatives pulled black tape on TUT.BY’s transparent office doors to prevent people from observing what was taking place inside and took a photo. Artem was quickly spotted and detained. A Minsk court later sentenced him to 15 days of arrest for allegedly cursing at a police officer. But in fact, he was punished for that photo.

But independent journalism will always find a way, Sviardlou insists. Belarusian journalists continue working despite the threat of detention. Those who have fled keep working too. They have only become more determent. When journalists find themselves in a safe environment, “their safety switches turn off,” as Sviardlou says. They begin to express more openly what they could not afford back home in Belarus.

But independent journalism will always find a way, Sviardlou insists. Belarusian journalists continue working despite the threat of detention. Those who have fled keep working too. They have only become more determent. When journalists find themselves in a safe environment, “their safety switches turn off,” as Sviardlou says. They begin to express more openly what they could not afford back home in Belarus.

Telegram channels play a crucial role in the Belarusian media environment. Research by the Center for European Transformation notes that the sharp growth of the messenger in Belarus began back in 2019. As protests erupted in 2020, Telegram’s growth skyrocketed. Telegram channels became, as Sviardlou puts it, “the main driver of information.” According to indirect data, in mid-August 2020, the messenger had over 2.4 million active users in Belarus, or roughly one-third of the nation’s total online audience. Urban residents accounted for over 60% of the users, according to researchers.

Today, the Belarusian media market is up for grabs by Telegram channels whose editors have long operated from outside Belarus, Sviardlou says. They’ve never been keen on following journalism standards. As their competitors, established media outlets upholding high professional standards, are being squeezed out of the market, Telegram channels with murky origins fill the gap. Belarusian independent news outlets do not publish information without verification, watch their language, and are generally more balanced, Sviardlou points out. But as Belarusian authorities force them out of Belarus, close down their websites, Belarusian remain with few alternatives than Telegram channels.

Another consequence of the destruction of the independent media sector in Belarus is the news aggregators coming forward. They publish everything chaotically. Their content is often trashy, devoid of government criticism.

Finally, Russian media are getting a huge advantage. According to sociologists, the Russian content has been in demand in bilingual Belarus, where up to 80% of the population uses Russian in everyday life. Researches suggest, that 25% of the Belarusian audience do not consume news from Belarusian media. At the same time, domestic TV channels are full of Russian content.

There is no money, but you just hold on.

Lack of money is another side to the story of struggling Belarusian journalism. Even before the crackdown, there were not many ways which Belarusian media could use to generate revenues. There were few success stories of the outlets sustaining themselves off ads sales – for example, TUT.by or Nasha Niva. But they have been destroyed by the. Starting anew, building the audience back, and attracting new advertisers will take a lot of time and effort. Part of the TUT.by team that fled Belarus has launched a new website out of neighboring Ukraine. Still, it was blocked in Belarus several hours later.

The way out is selling ads on Telegram, Sviardlou assures. TUT.by has 530,000 followers on Telegram, Nasha Niva – around 90 000. For example, Euroradio has begun generating some revenues on YouTube, too. Previously, Belarusian users preferred to watch high-quality Russian entertainment content on YouTube. Now, demand for analysis of the developments in Belarus, for interviews with experts has grown tremendously. Video chats with commentators on YouTube gather tens of thousands of views. ‘Correspondingly, we can now earn $700-800 monthly, which can cover some of our costs,’ Sviardlou says.

Donations are another way of income. Euroradio launched a Patreon campaign and crowdfunded 500 USD in donations in the first week alone. In Sviardlou’s view, the growing Belarusian diaspora plays a massive role as Belarusians living abroad are willing to support independent media to keep them rolling or help journalists move to a safer location. One of such initiatives is the Poland-based Media Solidarity Belarus, which allows newsrooms and individual journalists to pay fines or relocate to another country.

Lastly, the Belarusian news outlets that get funding from international funds are the least affected in the crackdown – at least, financially. “I think the donors have realized that donor support remains one of few existing ways for independent media to continue their existence in the condition of Belarusian authoritarian rule, which I believe is closer to totalitarianism. Advertisers are scared, but the number of private donators is not infinite. As a result, only institutionalized donor support can ensure media sustainability,” Sviardlou concludes.

People have realized why they need a free press

Large-scale political crises have a silver lining: people grow increasingly interested in current affairs and read the news more. Euroradio’s editor-in-chief confirms Belarus is not an exception. Since protests erupted, Euroradio’s audience has grown several-fold, including 8-times on Telegram and 5-times on YouTube.

But the most important thing is that “the audience became much more engaged and centers itself in the developing stories. We have been increasingly relying on user-generated content. Users offer leads, topics, questions, photos, and video footage, provide tips about the developments. For example, when security forces arrive at a newsroom of our colleagues, people from the nearby offices write to us, informing us about what is going on,” Sviardlou recalls.

“Everyone in Belarus is a journalist now. People have eventually realized what journalism is about and why it is needed. Fellow journalists told me that they had trouble finding camera operators in Belarus in the past because it was risky. But now, there is a line of willing average Belarusians who want to help those delivering the truth. We at Euroradio were able to hire several good journalists and parted ways with almost no one. By and large, people realize the risk but choose to go for it,” Sviardlou says.

Natalia Marshalkovich, Colab Medios Project